I might never catch a mouse

thinking of: Mike Kelley // Louise Bourgeois // Lias Saoudi // Bill Ryder Jones.

I wake around six, with him pawing my face. Outside the covers, a new cold. December has thickened becoming dark and damp and everyone’s descended on London, hoping for a little festive spirit and I am bad at knowing what that means, not having enough years of practice or memory. And soho is crowded streets and the impossibility of staying on the pavement for long enough to be safe from rikshaws and everyone looking at their phone maps, not realising any second someone’s about to swoop in and get that phone, the city full of magpies on mopeds. I like soho to myself. I do not want to share it with these people who will only gawp and take photographs, reduce it to spectacle. My soho is meetings and steak tartare to ease heartbreak - because how can you stay heartbroken with that amount of vitamin b12 in your blood (oh you can, it’s a temporary fix and too expensive a one to maintain, it’ll wear off on the night bus home, around five in the morning at just the worst of the worst times), it is burgers on a rooftop at 2am (so much red meat), it is basement clubs that fill you with dread as soon as you walk down the stairs covered with a swollen carpet, because you are walking over your own grave and one you’ve dug, again, it is sitting outside in the summer bumming cigarettes because you don’t smoke and drinking halves in the French House, of worse, bottles of cider. It is often a mistake. And mistakes are often where the best stories live. This might be why I like it.

Perhaps the Victorians were right to believe a photograph stripped someone of their soul; a tiny piece at a time, these tourists are taking a part of soho home that doesn’t belong to them, their lenses only concerned with the facades. And so I wake to the new cold that creep late last night under my thin jumper, my stupid coat, and the cat paws my face. I scratch under his chin. He lowers it for me, turns it slightly to the side; what he wants is a real scratch, not the half hearted I’m just awake now will you please leave me alone one I’m giving him. I scratch him harder, he begins his tired, mechanical purr. I scratch a while longer but my arm is cold. It needs under the covers again. I stop. He lowers his head, fixes me with the type of stare only a cat can. I refuse to believe Paddington had the hardest stare. I will not give in to this manipulation. I stare back at him. He plays his trump card, paws me with his right paw again, hard on my left cheek, his claws, partly out. I give in.

I read somewhere that what we think of as a gift from a cat, a dead mouse or a bird with its wings beating slowly to a halt, are not gifts at all but rather insults. The cat believing we are not able to fend for ourselves and that it must hunt for us. Does it watch us, foraging for foods in cupboards, opening Heinz soup, pouring beans into a pan? Does it worry how nonsensically inept we’ve become? Perhaps cats needs to come along to soho, to see the fights of survival on display on a night out, to join the hunt. Perhaps they would offer us less birds then, but likely, more, the doorstep piled with carcasses; the cat’s many implorations of please, please do better. I once had a cat once who used to hunt rabbits, her coat made sleek from their fat, she would leave a perfect cross section of the rabbit on the doorstep for my mother and me; always the hind part, never the head; that way we never had to deal with accusatory glassed over eyes. I fear the cat knew things.

Maybe a gift isn’t what we think it is. I wake to this cold and check my phone and a friend has sent me a sermon and the cat tries to flick my phone out my hand as I read it. This sermon reminds me of things I’ve known but forgotten and needed to be reminded of. Of waiting and return. It is in the darkness that faith’s needed the most, and I am not talking here of religious faith, but of the essence of faith itself, which is to behold as if real things not yet beheld, which at this time of year, is to believe that once again it will be light. I hate the dark. Dark nights, dark days, dark hallways, dark corners; in December the dark becomes so absolute that flicking on a light only makes it worse, it skulks off to a corner where it waits. My middle name means light, this makes it impossible to like the dark. This sermon is not wrapped in a box or held with bows, it is more carried in a mouth, deposited on a doorstep, there because sometimes I cannot feed myself the things I should.

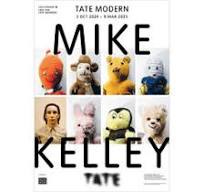

And a few days before that, I went to the Mike Kelley exhibition at the Tate Modern, and I still can’t quite work out how to articulate exactly what I saw. The scale of it felt almost like an action movie, pushing the boundaries of what it’s possible for the eye to absorb. It was so much. It was too much. It was perfect, especially for this time of year when the brain unwinds a little, becomes slow from cold, less sharp than it needs to be. These external things, they sharpen. The strength of the exhibition lies in the limits of Kelley’s preoccupations. On the wall outside the exhibition is a quote from Kelley, all you really do now is work with the dominant culture, flay it, rip it apart, reconfigure it. This becomes an epigraph and a manifesto, guiding the viewer through the exhibition and the many mediums Kelley used. It would be a mistake to think that in focusing on culture Kelley is venerating it, he is as excoriating as he is unflinching as he is unforgiving; his eye is not one you want to fall under. And like most artists with a narrow preoccupation, there is depth to be found in the consistent mining of the same seam. Kelley hits gold in his textile banners, creating proclamations both encapsulating the dominant culture and rendering it meaningless in the same piece, in much the same way Jenny Holzer does with her series of Inflammatory Essays pasted to the wall two floors up, although I notice three days later that one set of the essays has been replaced by new proclamations, perhaps the originals too inflammatory for a gallery increasingly dependant on pleasing shareholders. My favourite of Kelley’s banners where the one saying FUCK YOU in the centre, with, now give me a treat written along the bottom; perhaps epitomising many protest movements unable to incur any actual risk, but rather begging for reward. The other, black and white, PANTS SHITTER & PROUD. JERK OFF TOO, mostly amusing since I was on my way to a Fat White Family gig, which if you’ve ever seen Lias Saoudi play, you’ll understand. Lias is one of the finest performance artists working today, and his work has a close affinity’s to Kelley’s in that it doesn’t skip a beat or flinch for decency. Likely, it was easier for Kelley to make this kind of uncompromising work that it is for Saoudi to continue to make his, since the dominant culture today is more likely to flay the artist, rip them apart and configure them than give the artist the chance to do the same.

The brilliance of Kelley, Saoudi and Louise Bourgeois, whose retrospective at The Hayward Gallery in 2022 was the last thing I visited that undid me in the same way this did, is that they expose something of the artist’s minds - an act of generosity best described as a gift, even if Saoudi wears braces not bows. One critic described the experience of the Kelley exhibition as a bit like being flayed alive, giving it two stars. I think Kelley would be happy with this, in much the same way I enjoy bad Goodreads ratings when they perfectly nail how I wanted the reader to feel. Louise Bourgeois says it’s not about what something means, but how it makes you feel. It’s easy to sleep walk, art kicks us awake.

A lot is said about memoir being brave or revelatory or exposing but I’m with Molly Brodak when she said the facts are easy to say; I say them all the time. They leave me out. Read The Last Days and you’ll know what happened to me. Read this and you know I was at the Tate, the Fat White Family, in soho; these facts amount to all that David Copperfield kind of crap. The I of them only a narrator, removed from the self and operating outside of measurable time, existing in tense only, itself is an artifice. Work that takes real risks lies in exposing the interior along with the artist’s recurring preoccupations. Any obsession is difficult to reveal without incurring a risk. A generous artist is the one who risks exposing themselves; in the same way a gift exposes the giver more than any one else. It is no accident perhaps that the artists who seem to demonstrate this most consistently are artists concerned with the body and the things forbidden to it, or at least taboo to it; artists who understand that skin presents its own occlusion, being a barrier to the interior. These artists work under the skin of things, peeling back the veneer. I wrote on my phone notes when walking around the excellent Helen Chadwick exhibition peel back the exterior. See under. Not on the nose. Earlier in the week, Bill Ryder Jones spoke at The Social about love songs and how easy it is to write one that’s on the nose, how difficult it is to present a universal experience as something else. On Wednesday, I walked around the Olympic Park in Stratford listening to the Arctic Monkey’s I Wanna Be Yours. Sometimes I forget what a deeply weird but brilliant lyricist Alex Turner is; I wanna be your leccy meter, I’ll never run out perfectly articulating a sentiment a ham fisted lyricist would make obvious. Although obviously Bill Ryder Jones was talking about himself at this stage, and I went off to listen to Arctic Monkeys, but only really because I’ve listened to lychyd Da faithfully all year. If Tomorrow Starts Without Me is a perfect love song. The limits of human experience are just that, I taught earlier in the year about articulating the ‘inconsolable experience’, there aren’t many of these experiences, they’re consistent, and repetitive and happen to all of us and run the risk of being mundane, which is why we all want to articulate them; perhaps a way of saying me too, or only me; hard to know which. I don’t want to know your heart’s broken, I want you to break my heart too. I don’t want you weeping on the night bus, I want to weep there too (this is a lie, I’ve done my time). The beauty in expressing these events lies in the way Kelley does through using the depth of the narrow, and the way Bill Ryder Jones does and the way Alex Turner does, I wanna be your Ford Cortina. Carver wept.

This is maybe what’s taken me nearly a year after the publication of Ava Anna Ada to realise, that fiction is its own exposure, not always, but often, because it rests on interiority; the text pure subtext; and the uncanny a vehicle for what lurks out of sight but also in plain sight, right there for the reader to read, to infer. Which might also go a long way to explaining why I’m hesitant to finish my next novel. I worry I’ve gone too far. Ava Anna Ada is quite far, I said to my editor last week, when I explained the premise of the next novel, explaining too my worry of going too far; you’ve gone quite far, he said. But then I stand and look at Kelley, and I sit and write about Louise Bourgeois and I watch Saoudi jerk off on stage and I don’t know; there’s always further to go in laying it flat, making the culture look back at itself even if it doesn’t want to. Especially if.

I mean, I hesitate to recommend anything to the one who consistently steers me to my next read, making me wonder how I ever lived without it...but Ali, something here reminded me of Richard Brautigan's short, 'I Was Trying To Describe You To Someone'