Earlier this year, I wrote an essay for The London Magazine on Louise Bourgeois’ Femme Maison. Like much of Bourgeois’ work, Femme Maison is a series spanning a number of decades, executed in various mediums. Bourgeois measured success in how close she’d come to saying what she wanted to with her work, which is why she often returned to the same ideas and themes, feeling that she hadn’t successfully said what she wanted to. I sometimes wonder if this is why I rewrite so much. I’m quite brutal to my work. I will happily tear up a whole draft and start again, the distance between what I need to say and what I do say, often too wide. There’s a feeling a book is never finished, that there are many ways to narrate it, and I have often settled on the wrong one. Because of this, I struggle to read my published work, when I do, a sense of abject horror takes hold.

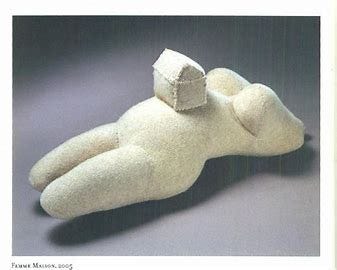

The Femme Maison piece I focused on in the essay was the final incarnation; a headless female torso made from boiled patched wool. I like this piece because it’s typically ambiguous, the torso at first appears pregnant with a house like structure protruding from the womb, but look more closely and it’s possible to see the structure is placed on the torso’s stomach, the weight of expectation pressing on the female form, attached by a series of tiny careful stitches. Femme Maison explores the female body as architecture and the weight placed on it by society. This is something I’m currently thinking about in my own work, so it’s inevitable this piece led the way. But while researching the essay, I went into all the other pieces in the series, trying to connect each, not just to the other but also to Bourgeois' life.

Bourgeois began the series in the 1940s, when her children children were very young. The genesis of the series a trio of disquieting paintings, featuring a female figure obscured by a house. Of this figure Bourgeois said ‘she shows herself at precisely the moment she’s trying to hide’. And there was something in this, shortly after finishing these paintings, Bourgeois didn’t have a public solo exhibition for nearly a decade, as if in trying to hide herself in her work, she’d given more of herself away than she felt comfortable doing.

I write from life and I write fiction, I often feel like my fiction is more exposing than my life writing is. When I’m writing from life, I’m hyper aware of the expectation (mostly placed on women) of the writer to give a lot of themselves away. At times this can feel almost pornographic - what’s the reader experiencing vicariously? Where’s the play between concealing and revealing, between hiding and exposing? For me this play is essential, just because someone knows what happened to me, doesn’t mean they know me. I like the dichotomy of writing memoir and being an intensely private person. I’m taking this play further in my next manuscript, using Barthes’ idea that it must all be considered as if spoken by a character in a novel. Life writing centres around true events, but that doesn’t by default make it true- as a narrator of your own life you’re already unreliable. But it’s in fiction, when my characters are speaking that I often feel the most exposed, when the I isn’t anywhere close to me; when I’m hiding, I am also not. This presents a peculiar degree of risk.

I feel exposed when I’m writing here. Partly because there’s no editorial intervention, partly because there isn’t a plan behind this, I just like doing it, partly because there’s very little distance between the I writing this and the you as the reader, partly because there’s nowhere to hide, and partly, over the last week, because there’s more of you than there were. When I write, I like to imagine I’m writing to one person, two at a push. I find the idea of readers almost paralysing. I wrote for ten years without an audience. The shift from perceiver, where I could see things and record them, to perceived, where my work is seen, critiqued and talked about, has been a strange one. Of course I need readers, and I’m very happy to have them (you), but I also have a strong urge to run away and hide as soon as I know there are some. I’m keeping the why to myself, but I often think about Bourgeois’ decade, where she wrote obsessively, not for anyone, not to anyone, covering every surface she could find in fragments, recording dreams, days, thoughts, creating a rich library of work she returned to in the following years, often to stitch into later work. I like this idea, I think maybe my decade of rejection will become something similar, I return to that work because it doesn’t yet say what I need it to. I haven’t yet said what I need to. I think the distance between what I intend to say and what I do say will always be vast, too vast for me to think I’ve successfully said it, and so, despite how uncomfortable it is to be perceived, I keep going.

Ali, I find it interesting that you refer twice to what you “need” to say, as well as what you intend to say, which suggests there is a motivation prior to, and different from, intent. Maybe you could say more about this some time, as motivation to write is something I am interested in, and particularly in how it differs between writers. Why do we do it? For my own part, I don’t know - maybe just curiosity to see what happens when the pen scrapes the page.

As I write my unspectacular memoir I often become frustrated with my desire to write the narrative but too often I’m overcome by the need to write the philosophical. The result usually becomes disorganized bit of waste in garbage can.